Commission for Prison Audit: can it really change anything?

The government has established a commission to audit local detention facilities; which has, even now, found critical information in its evaluation

The \'Commission for Prison Audit\' has reviewed the Malé Prison in January, 2019

On January 15th, Maldives woke to news of yet another death at a state-run detention facility. A 23-year-old woman, held at the custodial centre in Dhoonidhoo island over a theft case, passed away under suspicious circumstances that the police say they are investigating.

The Maldives Police Service said that they would be conducting an autopsy, and have asked for involvement from statutory watchdog bodies, the Human Rights Commission and the National Integrity Commission.

However, the investigation was impeded by the detainee’s family refusing to authorise an autopsy, and she was buried on January 16th without adequate inquiry. The police said then that ‘all the rights’ due to her had been guaranteed and she was given access to medical care.

In recent years, the Maldivian government has come under fire for alleged negligence over frequent deaths at local detention facilities. In June 2018, Malé native Ali Abdulla, a 30-year-old serving a life sentence on drug charges, was reported to have died ‘suddenly’ from no obvious causes.

Abdulla's family blames the Maldives Correctional Services (MCS) for his death, claiming that officers had refused to allow him access to medical care. A day prior to his death, Abdulla called his mother and complained of ‘cramps’ in his stomach.

33-year-old Ahmed Irushaad, who had also been sentenced to life over drug charges, died from a heart attack in January last year. Irushaad’s was the eighth inmate death in two years. The MCS, to this day, has refused to comment on the matter.

In October of 2017, 51-year-old Abdulla Rasheed died while serving the last year of his sentence over assaulting a police officer during the infamous 2015 ‘six-day protest’ in Malé. The state investigated allegations of negligence but the Human Rights Commission is yet to forward any charges.

In July, 2017, 52-year-old Mohamed Badeeu, serving a 10-year sentence over theft, died at the Indira Gandhi Memorial Hospital for reasons yet unknown. In December of 2016, 55-year-old Ahmed Hassan was found dead at the Asseyri jail in Himmafushi island.

Over the years, inmates have died from unknown medical causes, injuries from fights with other inmates, and simply being kept from access to medical care. Whatever the reason, something is clearly wrong, and if left unfixed, custodial deaths could reach epidemic proportions.

Ahmed Mahloof, who is currently Minister of Youth, Sports, and Community Empowerment, served 10 months and 24 days in prison on charges of inciting violence against the government in 2016. Mahloof said he observed gross violation of human rights during his time at the high security prison in Maafushi island.

READ MORE: MP Mahloof stresses importance of transparent prison regulations

Then president Abdulla Yameen was accused of turning a blind eye while concerns over custodial deaths mounted. Civilians and non-profit organisations continued their call to address the problem, as then opposition Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) said it was compiling a ‘shadow report’ of custodial deaths.

"The crucial need for a medical examiner and the facilities to determine what leads to death in custody must be acknowledged and addressed by the government. Too many deaths are signed off as 'stroke' or 'heart failure'. This is sadly insufficient", a tweet from the Maldives Democracy Network, says. There were also tweets calling on the state to identify all custodial deaths.

In fact, Yameen’s negligence of human rights was one of the loudest rallying calls during serial protests against him. Perhaps the most famous inmate to have been denied access to medical care is former vice president Ahmed Adeeb, who is serving a decades-long sentence for multiple charges, one of them being an attempt on Yameen’s life.

MDP’s candidate against Yameen during September’s elections, Ibrahim Mohamed Solih, pledged to investigate and run an ‘audit’ of local detention centres, to be accomplished within 100 days of assuming office.

‘Commission for Prison Audit’

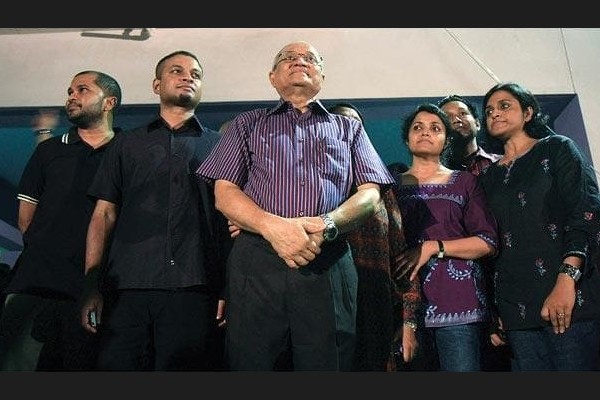

Members of the 'Commission for Prison Audit': prominent and competent

President Solih’s government established a 7-member commission to audit local detention facilities, both jails and prisons. The commission is looking into adherence to prison laws, individual prison regulations, international treaties, and reports compiled by statutory watchdogs and civil society organisations.

The ‘Commission for Prison Audit’ said in early January that it spoke with former chief justice Abdulla Saeed, who was imprisoned over fraudulent charges during Yameen’s tenure, and several lawyers. The commission has also received assistance from families of inmates.

On Thursday, the 24th of January, the commission released findings of its review of the Malé Prison. The four-page summary is incredibly telling; due to no emergency access to medical care, squalid conditions, being grossly understaffed, and lack of awareness among prison staff as well as inmates, the facility is ‘unfit’ for use.

The Malé Prison has no system for medical care and inmates could have to wait 30 minutes during an ‘emergency’, the commission has found. Their review also found that cell spaces built for four are used to keep up to 10 inmates, and in disrepair.

The ‘audit’ has also found that arrestees are brought to the prison’s custodial centre and kept for 24 hours before being released, without being charged or brought before a judge, and that convicts are not briefed on disciplinary methods that could be used against them.

The ‘Commission for Prison Audit’ is clearly doing its job, and is staffed with competent and prominent professionals. But can their findings lead to anything?

The Constitution of the Republic of Maldives gives the sitting presidents authority to establish inquiry commissions to advise them. The constitution also defines the scope of a cabinet and its members. President Solih has established two commissions under this authority, one to investigate deaths and ‘enforced’ disappearances, and another to recover misappropriated state assets.

But the President’s Office says nothing about the ‘Commission for Prison Audit’. It was the Ministry of Home Affairs that revealed its establishment and composition, on December 18th, 2018. Its findings and announcements are also uploaded to the Home Ministry’s website.

However, according to the Prisons and Parole Act, managing detention facilities is the mandate of the MCS, an independent body of ‘uniformed’ officers. An audit of detention facilities would therefore be a review of the MCS, which under no law or regulation, falls under the mandate of the Home Ministry.

Audits of state institutions and government offices are also the mandate of the Auditor General’s Office, which according to all available information, has nothing to do with the ‘Commission for Prison Audit’. It is also the state auditor’s reports that are used for investigations and policy making.

The Prisons Act was ratified in 2013, and while it makes mention of a ‘minister’ to which the MCS has to report to under certain circumstances, neither the statute nor regulations derived from it defines which minister it is. Therefore, making the audit the mandate of the Home Ministry seems to be a decision based on past custom alone.

The commission is carrying out necessary work. Work that will undoubtedly change the existing situation for the better, but one that seems to be without solid legal foundation. It would serve the state well to define such matters more clearly, to make them more substantial and systematic. As of now, the Maldivian people have little guarantee that the commission’s findings will have lasting impact, and is not just elaborate political rhetoric, the guarantee being the word of politicians.