A code of conduct for parliamentarians?

A code of conduct would be an important element in fostering public trust in, and improve public perception of the People's Majlis and its members

Parliamentarians at a sitting

All around the world, parliament floors are serious places and parliamentary sittings are serious ordeals. Members of a legislative body are required to dress a certain way, conduct themselves in a certain manner and to be addressed with certain honorifics.

However noble an undertaking it is to represent ones countrymen and deliberate on and pass matters that are to become law of their country, most politicians are grossly distrusted and too often the butt of jokes.

A 2016 poll conducted online showed dwindling distrust in the People’s Majlis, while trust in local courts have always stayed abysmal. In a country such as the Maldives, where the entire electorate is literate and has access to a wide array of political narratives, one would assume parliamentarians elected here are people that have won over their constituents.

But ours is a society that is suspicious of the motives of our elected representatives. In the past politicians who have filled seats in parliament have been known to go entire tenures without speaking, let alone submitting a draft bill or motion on behalf of his or her constituents.

This past batch of parliamentarians, who were elected in 2014 have had their hands full. While on one side of the political divide, lawmakers complained of a disrespect towards decorum and sanctity of the legislature, lawmakers on the other took matters into their own hands and protested injustice and government influence on the Majlis by demonstrating during sittings and later boycotting them entirely. While this did prove a point, and was for both sides a means to an end; it underlined what appears to be failure of the legislative system to adequately represent the people.

With less than three full months left until Maldivians will again go to the ballot box and elect a new individual, or vote to keep an incumbent, to their respective constituencies, a question to consider is should there be a code of conduct in place?

Such a proposition may seem idealistic, or even over zealous. What we have seen since November 17th is the slow-moving slug of parliamentary matters actually move; after a hiatus over political differences that really are petty in comparison to the plight of constituents who lack access to not just good education and adequate health care, but clean water and sanitation. And with political righteousness and rhetoric silenced, recent sittings have shown much.

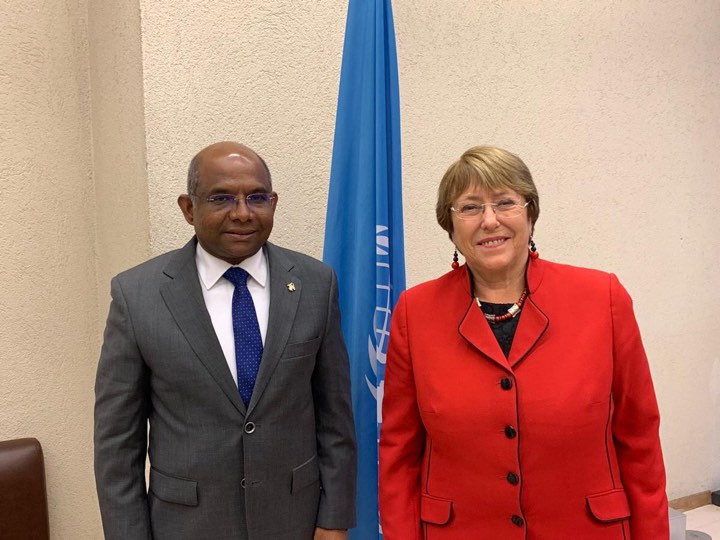

In the past few weeks, we have seen lawmakers aligned with a coalition which stood for ideals such as sustainability and clean development elect a resort tycoon whose businesses dump significantly more trash into Maldivian waters than any community to the helm of the house, lawmakers claim women were the property of men, and one suggest that immigration officials place trackers on lawful and documented expatriates as if they were cattle.

It is the constitutional liberty of MP Ibrahim Mohamed Waheed to say a woman always belongs to some man, or for MP Ali Arif to claim his idea to tag expatriates is ‘good and novel’ - so however distasteful they appear such differing narratives are essential to a functioning democracy.

A code of conduct that is proposed here does not wish to silence MPs Arif or Waheed but to introduce a written and enforced mechanism to ensure that they and their peers abide by an ethical standard.

This code of conduct should regulate lawmakers not just in financial matters but bar behaviour of members that may tend to thwart the operation of Majlis, abuse of the allowances, privileges and position of a lawmaker, and actions that may otherwise bring or be thought to bring into disrepute other lawmakers.

Lawmakers should present their earnings, they should be required to visit their constituencies or at least have a direct line to their constituents, they should be barred from shaming individuals or groups of society and should be subject to penalization for violation of these standards that is beyond public embarrassment.

Such a code, enforced by investigative mechanisms and disciplinary committees, should set public standards by which the behaviour of lawmakers can be assessed, provide a basis for assessing proposed actions and so guide behaviour, provide an agreed foundation for responding to behaviour that is considered unacceptable, and assure and reassure the community that the trust placed in lawmakers is well placed.

A code of conduct not just to regulate how MPs refer to each other or speaker of the house but one that bars them from decisions based on blind ideology, self interest and pressure groups and forces them to stay true to the needs and aspirations of the communities they represent.