Power of Population: an appeal for decentralization of development

The bulk of state-funded shelter programs focus on the capital city and Kaafu atoll

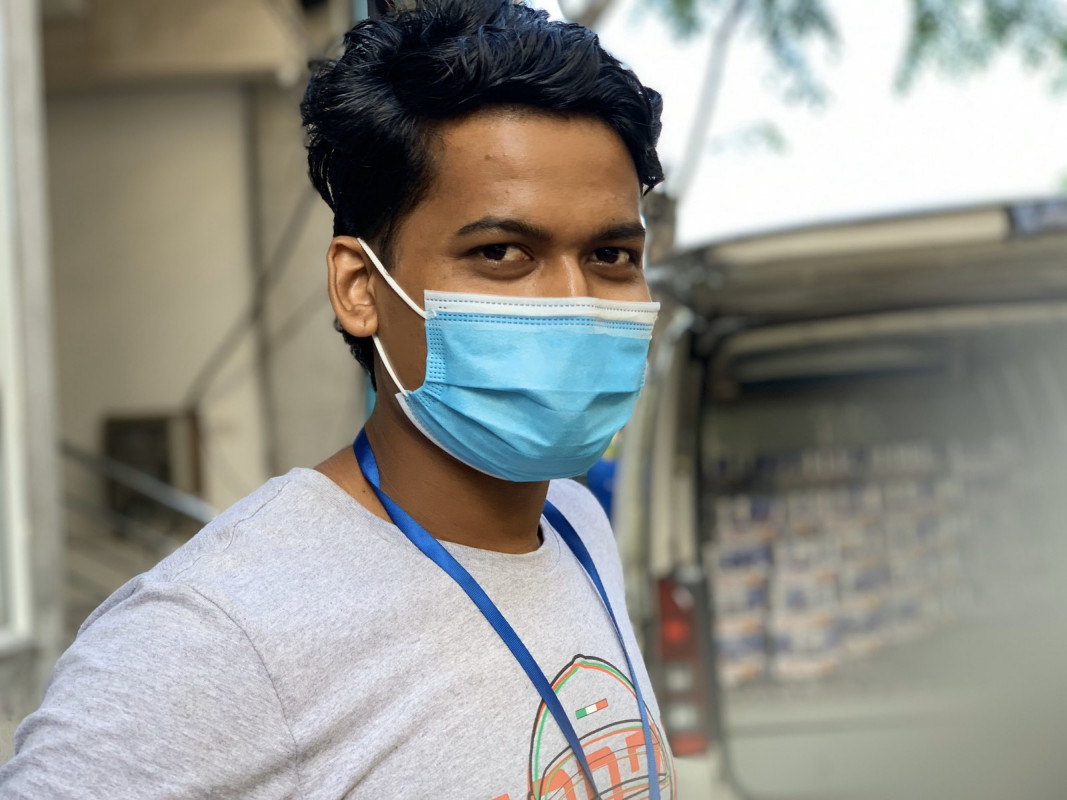

Incumbent President Abdulla Yameen speaking at an event to launch the state-built flats in phase II of Hulhumalé, the capital city\'s urban extension

Historically, all governments that the Maldives has seen have run state-supported shelter programs. It comes naturally; Maldives is mostly water and coral rock, land is scarce and its understandable that people need better housing.

What strikes strong about these projects is that the bulk of it focuses on the capital city and Kaafu atoll, known now under the Yameen administration as the ‘Great Malé Area’. Sure, there are flats developed in other islands to the north and to the south but most of it is in the capital but most of it for native Malé residents or those that are signed on with the 'Dhaftharu', and are thus officially natives without land.

The most prominent shelter program run this year has been the ‘Hiyaa’ project. Thousands of flats are to be given to young married couples, local teachers, law enforcement officers, and civil employees. These flats are all to be given in Malé.

While these projects are focused in the capital city, they are not solely built for natives of Malé. In fact, a bulk of flats, about 2,000, are to be given to none-native residents of Malé – people who have resided here for extensive periods.

The ‘Hiyaa’ project has already been dubbed a success by Housing Minister Mohamed Muizzu and his office has launched its successor, the ‘Hiyaa Accomplished’ – which gives out flats built reclaimed land in Kaafu atoll’s less urbanized islands.

Why are so many people flocking to Malé? One of the most densely populated places on earth, commuting is tough, streets a packed with people and noise and and even the most ardent observer of traffic laws will be hard pressed to avoid committing a violation. Census’ carried out by the government say it is mostly for employment opportunity, then for education, and access to medical facilities.

Ultimately, it is a matter of choice or the lack of one. In 2017 alone, RaajjeMV itself has reported on several accounts of medical facilities in the out lying atolls underperforming, with one father blaming his negligent doctor for ‘letting’ his unborn child die in its mother’s womb. In Kulhudhuffushi, over 300 islanders took to the streets staging a protest against the Health Ministry over deteriorating health services there.

Therefore, it is easy for people starved for such facilities to feel lighter when they hear that their president or government is giving them an opportunity to reside in the capital, where they can find employment for better pay, give their children better education, and have better access to medical care.

Not all islands can be developed tertiarily, true. Maldives is an archipelago of about 1119 islands spread across various atolls and some are too small and far in between with too little a population to warrant a large hospital, a school with well-paid staff, or for big businesses to be set up.

But why are there no quality services in southernmost Addu or in Huvadhoo, save for privately owned ones? These are large chunks of land with thousands living there. The long-term the social and economic ramifications of such centralization can prove to be detrimental but for now, development seems to bank of one thing, how many votes can be gotten out of it and money for such projects seem to flow directly parallel to how much political capital can be exploited out it.